For the past 20 years a common saying in the commodity space has been “If you build, grow or mine it, China will buy it”.

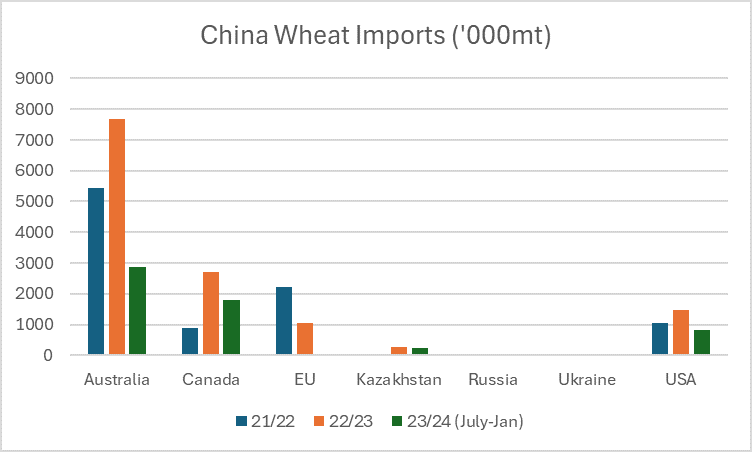

This is still somewhat true (barley and other previous tariffs aside) as the world’s largest importer of almost everything remains a colossus but the nature of China’s demand for commodities is starting to shift. The most glaring difference from 20 years ago is that China is becoming an increasingly price-sensitive buyer and appears more willing to use its purchasing power to try to influence prices. A case in point is the recent cancellation, or more likely the postponement, of Australian wheat shipments by China.

This is one of multiple mechanisms that China uses to directly influence local, and global, prices but there are also other ways they indirectly affect markets which is something I thought would be worth delving into. Before we get started, however, here are some interesting Chinese stats to ponder (one caveat though – sometimes data from China needs to be taken with a small grain of salt):

- It is the most populous country in the world with 1.4 billion people (35 million of those live in caves!).

- It is the world’s largest grain importer and consumer despite producing over 650mmt per year itself.

- It has the second-largest economy with a GDP of $16 trillion.

- It is the third largest country at 9.6 million km² and has the most international borders at 14.

- They have the longest high-speed railway network (over 42,000 km) that could loop the entire world 3 times.

- They were the first, and probably the only, country to sell live crabs out of vending machines.

- Half the world’s pigs (450 million) live and then get eaten, in China.

In terms of the effect China has on global commodity markets, and why we rely so heavily on our trade with them, it is the first and last points on the list that are the most important. They have a lot of people to feed and to feed them, they have a lot of animals which also require feeding.

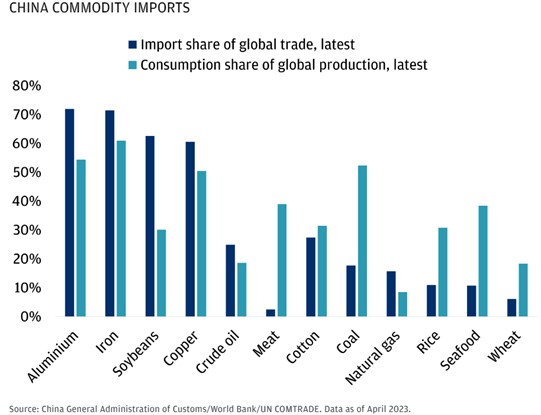

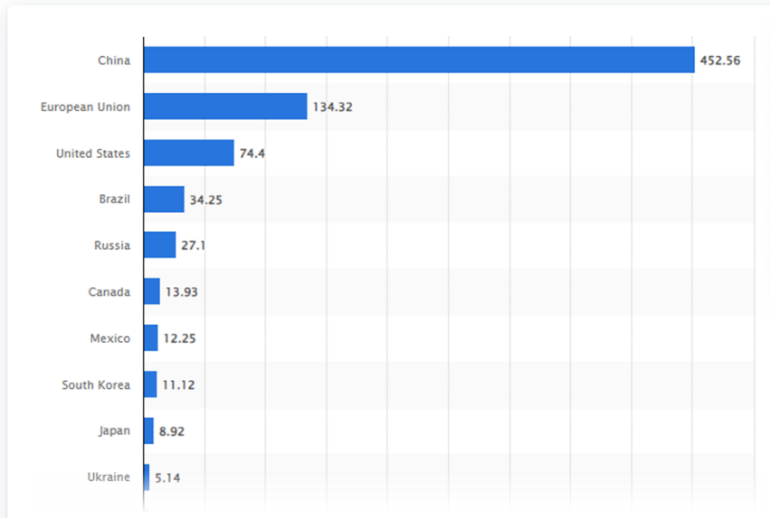

Over the last two decades, China has developed into the largest importer of agricultural products in the world. Apart from the massive population itself, this growth is mainly due to rising living standards and shifting consumption patterns towards protein-rich food, fruits, and vegetables. China’s influence on global commodity markets can’t be overstated as they dominate global trade. This is true for agricultural commodities but also across the energy and mineral space as per the chart in the next column.

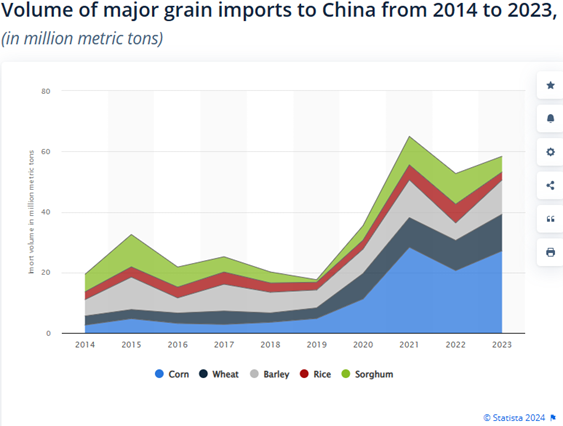

If we drill down to just Agricultural commodities, the picture is the same. China takes around 61% of the world’s soybean , 87% of the sorghum and 29% of the barley imports. They also account for 12% of the world corn imports and 6% of the world wheat trade as per the below chart:

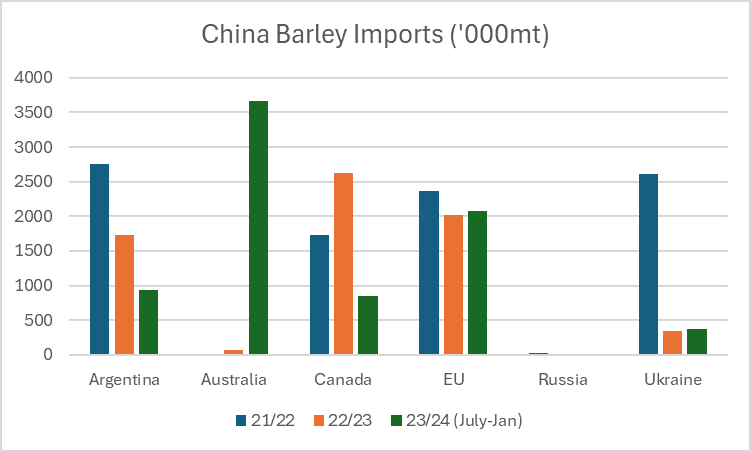

And if we focus just on Australian wheat and barley, the charts below give us a snapshot of just how much we rely on Chinese demand for our grain.

You could be forgiven for thinking that this reliance is a two-way street, but we only have to go back to 2020 when China imposed a ban on our barley to know that they will always go elsewhere for their grain if the price, or the policy, demands it. That decision had a direct (and detrimental) effect on our local barley prices.

The other elephant (or in this case pig) in the room, in terms of affecting global markets, is the size of China’s pig herd which acts as a major driver of global grain prices. Their vast demand for feed grains significantly influences the supply and demand balance in the international market. As of April 2023, China was home to more than half of the global pig population (as per the chart below) yet they cannot satisfy domestic consumption and import up to 2mmt of pork/year.

Pigs are primarily fed grains such as corn, soybeans, sorghum and to a lesser extent, wheat and barley so any fluctuations in the herd size will have an impact on the demand for these feed grains. As a result, the economic and physical health of the Chinese pig sector severely impacts global supply. A downturn in the pig sector late last year triggered a rush to slaughter by farmers battling plummeting prices for their livestock, high costs and an outbreak of African Swine Fever.

This is one of the major drivers behind why soybean prices are currently under pressure. Soybean demand is reduced, carryover stocks increase, and this then flows onto the other vegetable oil complexes such as canola.

To wrap things up, it would be remiss of me not to use another common quote attributed to Klemens Von Metternich, a prominent 19th-century diplomat, who coined the phrase “when France sneezes, Europe catches a cold” during an era when Europe dominated the world. During the last century, this morphed into “when America sneezes etc.” as the US became the dominant figure in world trade.

It could now be argued that over the last 20 years, it has been the economic health of China, rather than the US, that has the largest effect on global trade. Despite the recent speculation surrounding the health of the Chinese economy, it continues to strengthen its food supply resilience both domestically and internationally and, as a result, continues to dominate and/or influence global commodity markets. But, as we have witnessed recently with the removal of the barley tariffs, any shifts in China’s demand, policies, or trade relations with any of their major trading partners can have notable effects on Australian grain producers, exporters, and prices.